HONOURS AND AWARDS 2021In recognition of valued service to the educational emancipation movement for Indigenous peoples and the pursuit of dignity, well-being and the reaffirmation that Indigenous peoples, in the exercise of their rights are free from discrimination. |

The Order of the Circle of Chiefs of Indigenous Leadership |

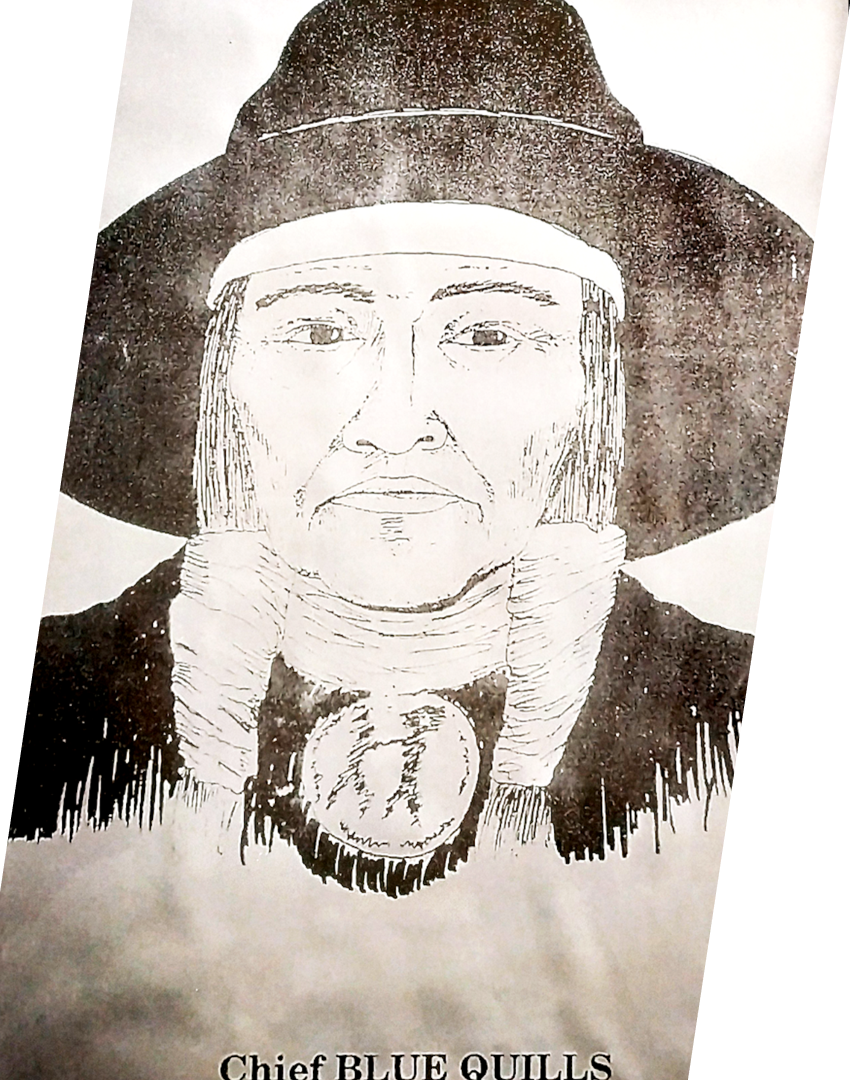

| Chief Blue QuillChief Blue Quill (sîpihtakanep) sip-i-tak-anep was among the original four chiefs that were forced into an amalgamation to form Saddle Lake as a result of signing Treaty Six. Chief Blue Quill settled on the western end of Saddle Lake. The Chief was known as a compassionate man and the only chief of the 4 who agreed to a school to be built on his portion of the reserve “There were two religions at that time – Protestant and Catholic,” Elder Stanley Redcrow stated to the St. Paul Journal. “The Catholics went to school at Lac La Biche (65 miles/ 105 km north), and my father was one of those guys. When they went there, they never came back until they were 16 years old. At that time, the road was very bad; all they could use were dog teams. It happened quickly. The Federal Indian Department studied the school, and in 1898, moved it to the more populous Saddle Lake. Within a year, a pair of Oblate brothers had built and dedicated a church and school at Saddle Lake, with the help of the people. They called it Blue Quills, and the reasons, as Redcrow notes, are interesting. “The government said they could build the school at a site, but when the Protestants saw those piles of lumber, they asked what we were doing. We said, ‘We’re going to build a school here.’ They said, ‘No, you’re not. After you pile the lumber we’ll put a match and burn it up.’ All four Saddle Lake Chiefs; pakan, onchaminahos, Blue Quill and Bears Ears, were of the Protestant faith. The Oblate fathers went to see Chief Blue Quill and told them they wanted to build a school. Alphonse Delver, a direct descendent stated that Blue Quill responded to the request affirmatively, “Yes, put it on my land. I’m thinking of the future of my grandchildren and the orphans.” William Delver, son-in-law married to Chief Blue Quill’s only child Nancy, saw the future of the grandchildren and great-grandchildren whom he said would live during a time when, “kipimâcihonâwâw ka-wehcasin. kinehiyâwiwinâwâw wî-âyiman ka-miciminamihk. (Earning a living will be easy. Being Cree will be hard to hold.) In 1931, the school was moved to its present location, 2.5 miles/ 5 kilometers west of the town of St. Paul, Alberta. More than 90 years later, the brick building is still standing, the site of a First Nations owned and governed University. Descendants of Chief Blue Quill are among the students and faculty at the university. |

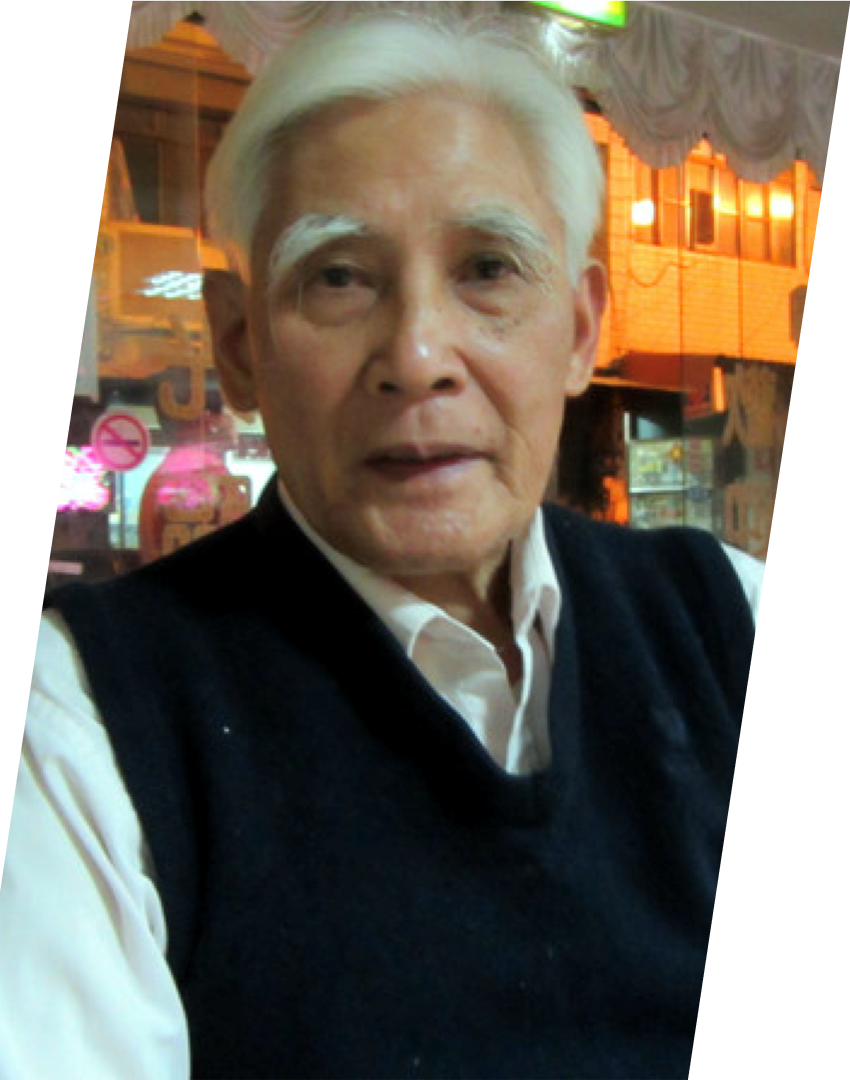

| Dr Peter HanohanoPeter has been a significant part of the WINHEC community. Peter completed his undergraduate degree at Brigham Young University Hawaii, and graduate degrees at BYU in Provo, Utah, in Educational Psychology (MEd) and Law (JD), and his PhD in First Nations/Indigenous Peoples Education from the University of Alberta, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. His dissertation title was: Restoring the Sacred Circle - Education for Culturally Responsive Native Families that described culturally resilient factors that Indigenous families could incorporate in creating enriched learning environments at home. He has been involved with Native Hawaiian and Indigenous education for several decades, and was Commissioner on the Hawaii State Charter School Commission. He has been a very active member of WINHEC, and has also undertaken a number of WINHEC accreditation visits, including here in Australia where he was part of the Wollotuka accreditation visit. Peter sees the world through such an inspiring Indigenous lens. Sadly, Peter has been very unwell this year which is why he is not with us today, we send him our prayers and best wishes. This award recognises Peter’s leadership in both WINHEC and WINU most recently as the Vice-Chancellor of WINU and also his long-standing leadership within his communities. He provides such strong mentorship to our future leaders, his approach is completely grounded in cultural integrity. Not only was Peter part of the foundational Leaders to progress WINHEC but it was because of his diligence and dedication that WINU was able to be established as a legally founded university which also embraces the sovereign rights of Indigenous Peoples as outlined in the UNDRIP. |

The Order of the Circle of Elders of Indigenous Wisdom |

| Aing BandayAing Banday’s late husband is one of the movement leaders. Aing Banday participated in this movement by devoting her time to learn ni tenunan tu benina in her 60s. Aing Banday holds the knowledge in traditional indigenous weaving techniques. She specialized in her Kavalan Nation’s “ni tenunan tu benina (banana fiber fibric) weaving and has recently been recognized by Taiwan’s the Ministry of Culture as Taiwan’s Important Traditional Crafts’ preserver with title of National Living Treasure. The Kavalan "ni tenunan tu benina," is representative of the craftmanship of the Kavalan peoples. Traditionally, they would perform a traditional ritual before cutting the pseudo stem of a banana plant to make the fabric. Aing Banday, a second-generation weaver, dedicated herself to revive “ni tenunan tu benina” in the Kavalan Nation. She is familiar with the skills and tools used for weaving with banana leaves and is also able to perform the traditional ritual, known as paspaw, to pray for blessings from their ancestors’ spirits. In 2019’s WINHEC AGM, Aing Banday and her team provided service to one of the community tour visitors. The preservation and inheritance of Taiwan’s important intangible cultural heritage is an important mission for Indigenous education and worldview. |

| Pan Wan-ChinPAN Wan-Chin passed away in May 2021. He has been a great and respectful local leader and activist. He took pride in passing on Taivoan culture tradition through oral stories. He also led his people to restore traditional ritual and songs since 1990s. With his endless efforts for more than 40 years, he has been recognized as an important local knowledge holder and elder. Under his leadership and activism, Taivoan people the local government recognized as indigenous peoples in 2013. |

| Uncle Stan Grant (Snr)Uncle Stan is Senior Elder, former Chair and continuing mentor for the Wiradjuri Council of Elders. He is a man of great wisdom and through his leadership, generosity of spirit and dedication, the Wiradjuri Nation is self-determining our futures with strong connections to country, culture and language. Through his vision Uncle Stan has led the Wiradjuri Nation on a journey of cultural and language reclamation. His profound legacy is all inclusive with a footprint which takes education influence from primary to secondary and into the higher education sector. From our young ones in primary school, to those wanting to undertake higher education Wiradjuri language is now at their fingertips, within the classroom and the community. His knowledge base come from his own childhood life experiences and he has authored reminiscences of life growing up in Wiradjuri country with knowledge holders who held the traditional values and beliefs of their forbearers. His recollections from his childhood have had a powerful impact on understanding the nuances of traditional ways of being and ways of doing in Aboriginal histories. His good humour holds the stories with reverence and humility whilst guiding his audience to see the value of social histories within our cultural narrative. Further to this, growing up with Elders who were language speakers created a dedication and a vision in Uncle Stan to see this again in his nation and led to his work in creating the Wiradjuri Dictionary. Uncle Stan has mentored many and is dedicated to the Wiradjuri community, the community of scholars at Charles Sturt University, who honoured his work with an honorary Doctorate of Letters in 2013, and those within other institutions cross the Wiradjuri Nation and Australia. His acumen in terms of Indigenous knowledge holds him in great respect and acclaim, with national recognitions, such as Member of the Order of Australia and Deadly Award, for his dedication to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander education and Wiradjuri language. A man of great faith, great spiritually and a great love for all things country and western, Uncle Stan is one of our great educators, dedicated to community and country. His work ensures that Wiradjuri knowledges, Wiradjuri ways of being and doing, Wiradjuri language lives on. Through our communities, through our young people. |

The Order of Scholars of Indigenous Knowledge |

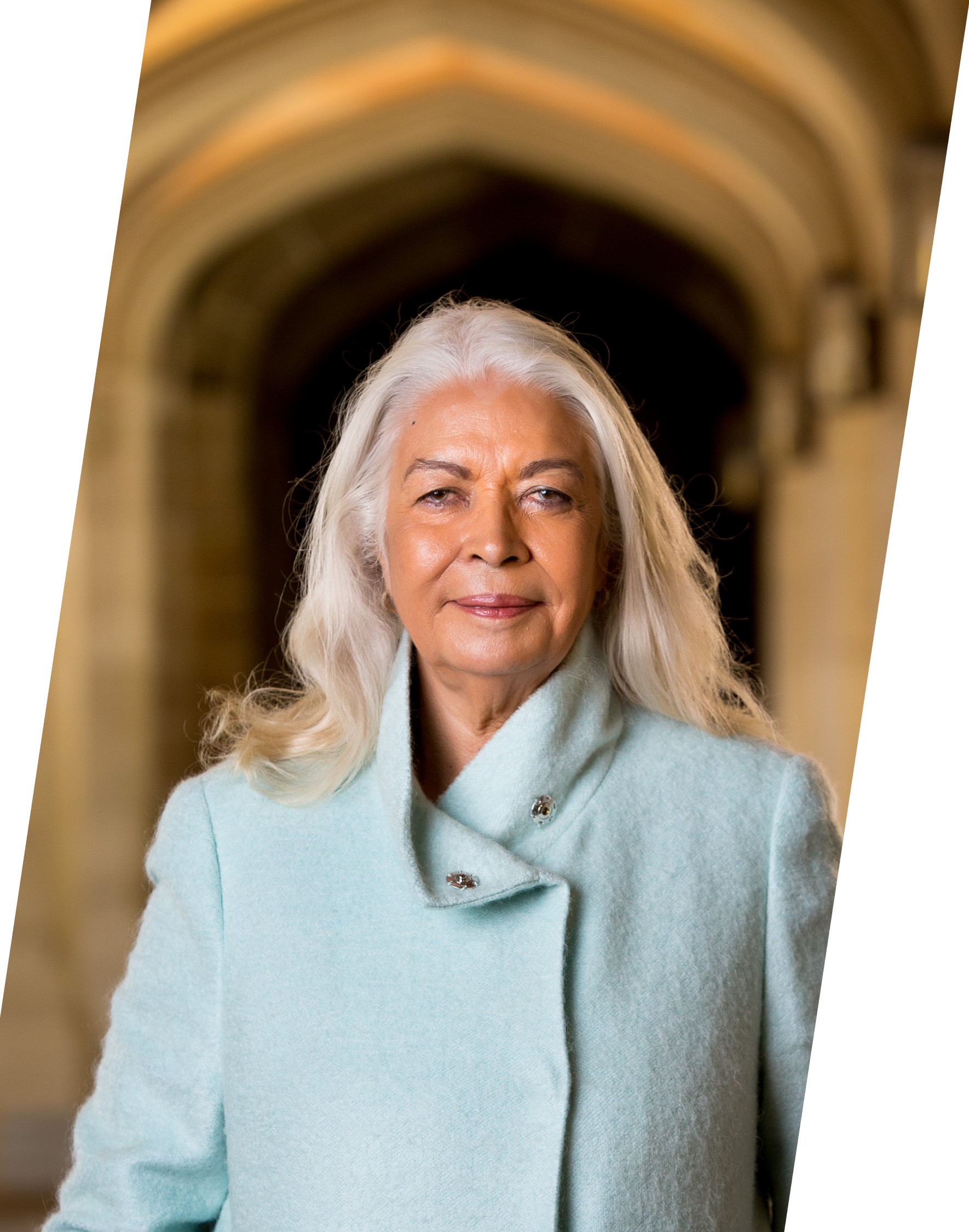

| Distinguished Professor Marcia LangtonDistinguished Professor Marcia Langton AM is an anthropologist and geographer, and since 2000 has held the Foundation Chair of Australian Indigenous Studies at the University of Melbourne. Professor Marcia Langton is a highly respected academic not only internationally and within Australia, but especially at her home institution, the University of Melbourne. Professor Langton’s contributions extend beyond her research and academic output, generously giving time to attend campus events, student gatherings, and she extends enormous support to Murrup Barak, the Melbourne Institute for Indigenous Development, which is the centre for Indigenous student recruitment and support. Professor Langton will often make time to speak with students one-on-one and never hesitates to make connections and offer advice when it is sought. Her cultural knowledge and authority as a Yiman and Bidjara woman is also highly respected. Professor Langton supports the academic endeavour at Trinity College, a private residential college connected to the University, as a Fellow of the College and is Chair of their annual Indigenous Higher Education Conference. Her role as Chair of this conference is significant in attracting experts, researchers, and the community to discuss pressing issues, highlight best practice, and celebrate success. Professor Langton invests strongly in building productive, reciprocal relationships including with local Aboriginal people in Melbourne, the Wurundjeri and Bunurong/BoonWurrung peoples, and the Yorta Yorta Nation in Victoria’s Goulburn Valley with whom the University has formal relationships via the Rumbalara Football Netball Club, a product of which is the Academy of Sport, Health and Education. Professor Langton guides the University’s relationship with the Yothu Yindi Foundation and leads the policy forum at the annual Garma festival, of which the University is a major sponsor. This is yet another brilliant example of how Professor Langton remains an influencer of public policy, a conduit between government and the academy, and is regarded as one of this country’s greatest contributors to social justice. Professor Langton has carved a path for Indigenous leadership to thrive not just at the University of Melbourne but across the sector. Her decades of work continue to be referenced, cited, and discussed for the advancement of Indigenous success around the world. In 1993 she was made a member of the Order of Australia in recognition of her work in anthropology and the advocacy of Aboriginal rights. She is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia, and an Honorary Fellow of Emmanuel College at The University of Queensland. In 2016 Professor Langton was honoured as a University of Melbourne Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor. In further recognition as one of Australia’s most respected Indigenous Academics Professor Marcia Langton AM was in 2017 appointed as the first Associate Provost at the University of Melbourne. Distinguished Professor Marcia Langton was nominated by members of NATSIHEC that held her in high esteem as an inspirational mentor, an activist and as an academic leader continually advocating for social justice and Indigenous rights. |

| Ron Indian MandaminAnishinaabe teachings are passed forward through blood line, active teaching, engagement and ceremony. Ron Mandamin has received his traditional knowledge in this manner. His blood line flows back and back and back. Ron holds traditional knowledge and passes forward that which he has been given. Ron is a highly respected Anishinaabe nini (man) who lives, leads and teaches from the traditional Ojibway ways he was raised. He speaks fluently, was taught the traditional teachings, history, plants, medicines, healing practices, language, and all Anishinaabe, as few have. Ron is known across Anishinaabe country and is highly respected as a presenter, ceremonial lead, orator, singer, teacher, language speaker, fabric and beading artist and the list goes on. He is a member of Iskatewizaagegan No. 39 Independent First Nation. Contemporary boundaries locate his community in northwestern Ontario, by the Manitoba border. Years ago, I encouraged Ron to gain credentials in the SGEI-Queen’s University Aboriginal Teacher Education Program. At the time, I was the Seven Generations Education Institute’s Post-Secondary Education Director. Ron was actively teaching without mainstream credentials and subsequently, not receiving respectful remuneration. Ron chose not to enroll in our program and I have come to understand a little bit of why he chose not to venture into mainstream-indigenized study. He carries Anishinaabe 3teachings in a pure form, taught in the language and with meaning as the Elders gave him. He did attend minimal mainstream education then chose to maximized the training he received from his Elders. From a young age, throughout his life and through spirit Ron continues to learn and teach. As such, I have relied upon Ron to lead ceremonies, be a guest speaker to students, assist in healing practices and present at various workshops and conferences. Ron is an extremely special Traditional Knowledge Keeper. In Treaty 3, I can think of no other person who carries the language, teachings and way of being as he does. He is a role model, humble and tenacious. Ron is the headman, Ogimaa for the Iskatewizaagegan 39 Midewiwin Lodge. The Midewiwin Lodge, good hearted way, he leads humbly, attracts Anishinaabe from across our territory. He carries songs, teachings, protocols, and so much more that he passes forward to the people. Ron empowers others by encircling himself with many oshkabiwis, helpers, who are learning through active engagement. His teachings impact lives as we listen, connect to Spirit, release pain, embrace love and laughter. Lives have changed because he has chosen to hold to the teachings, songs and gifts passed to him. He willingly passes them forward as - “These teachings belong to all of us. No one person owns these teachings, Creator loves us all.” |

The Order of Service to Indigenous Education |

| Professor Vuokko HirvonenVuokko Hirvonen is an indigenous Sámi. She is Professor Emerita of Sámi Literary Studies at the Sámi University of Applied Sciences (SUAS), in Kautokeino, Norway and honorary doctor for excellence in educational research (2019) in the University of Umeå, Sweden. In 1999, Hirvonen was the first to defend her dissertation entirely in Northern Sámi, and even since then she has published academic texts in Sámi, which has contributed to raising the status of the Sámi language as a scientific language. Hirvonen has also made important pioneering contributions in Sámi research in other ways, not least by introducing gender scientific and postcolonial perspectives in Sámi literary research. In her doctoral dissertation Voices from Sápmi: Sámi Women's Path to Authorship, Hirvonen showed that prominent female writers played an important role in the ethnopolitical mobilization of the 1970s in Sápmi. At the same time, she pointed out that Sámi women have often been marginalized in the literary sphere, as well as in Sámi society and the majority society. Hirvonen's research shows great breadth and is related to both the humanities and social sciences. In addition to literary studies, she has devoted herself to research ethics issues and educational research. She has also demonstrated a great commitment to bring forth new voices from Sápmi in both research and literature. Hirvonen has developed an extensive international research collaboration and contributed to making Sámi research visible in a wide range of indigenous research, gender studies and postcolonial studies. |

| Professor Ole Henrik MaggaOle Henrik Magga is an indigenous Sámi. He graduated in language research at the University of Oslo, with a focus on the Sámi language. In 1986, he became the first Sámi to get a Doctoral degree in research in Sámi. He has since worked as a professor of Finno-Ugric languages at the University of Oslo in 1987–1990, as an university lecturer, a museum lecturer at Tromsø Museum, a professor of Sámi language at the University of Tromsø and from 1997 as a professor at the Sámi University of Applied Sciences in Guovdageaidnu. Magga played an important role as leader of the Sámi language working group when the common Northern Sámi orthography was approved, and later on as well in several other Sámi languages. Magga was the leader of the Norwegian Sámi Association from 1980 to 1985, and the first president of the Sámi Parliament in Norway, from 1989 to 1997. Magga co-founded the World Council for Indigenous Peoples (WCIP in Canada in 1976), and in the period 1992–1995, Magga was a member of the UN Commission on Culture and Development. In 2002, Magga became the first chair of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples. Ole Henrik Magga has received several awards and honorary awards for his academic and political work, including Oslo University's Human Rights Award (2006), the Order of St. Olav (2006) and an honorary doctorate at the University of Tromsø (2008). |

| Associate Professor Kristine NystadKristine Nystad is an indigenous Sámi. Nystad has previously worked in the Sami Education Council where she contributed to the development of the Sami education system and has also worked at the Sami Parliament. In 2002 she started as an associate professor at Sámi University of Applied Sciences, and in the period 2003-2007, she was vice-rector. During that period and earlier, Nystad has worked to promote cooperation between indigenous peoples in education and research and has played an important part in the work of promoting Sámi University of Applied Sciences as an indigenous institution. In Nystad’s doctoral dissertation, ”Pathways to Adulthood”, she researched young people in Kautokeino in collaboration with an international research team that conducted similar research in the circumpolar north of Alaska (Kotzebue, Alakanuk) Canada (Igloolik) and in Siberia (Topolinoye). The project gathered, systematized, and analyzed the strategies of young people in the transition to adulthood in a rapidly changing society. This involved analyzing challenges young people face and what resources are used by the individual, in the family and local communities to ensure a successful transition for young people to adulthood. |

| Professor Clair AndersenProfessor Clair Anderson is a Yanyuwa and Gungallida woman from the Gulf country of northern Australian. She has worked in Indigenous education for over 30 years contributing to all areas of Indigenous education, learning and teaching, research and workforce development contributing extensively to improving policy and practice in these areas nationally to enhance student learning, to improve understanding of Australia's Indigenous peoples and build better futures. Her research interests are in improving education pathways for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, and the development of culturally inclusive curriculum to enhance understanding and improve delivery of health and education services to Indigenous Australians. Clair has been an active member of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Higher Education Consortium (NATSIHEC) representing NATSIHEC at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and has been a long standing member of the NATSIHEC executive. She is currently the Vice-President Indigenous Learning and Teaching for NATSIHEC and has held many leadership positions on national committees including the Ministers Indigenous higher education advisory council, advocating for the advancement of Indigenous higher education in Australia. |

| Professor Onowa McIvorProfessor Onowa McIvor is Maskiko-nehinaw (Swampy Cree) and Scottish-Canadian. Her Maskiko-nehinaw family is from Norway House and Cross Lake in northern Manitoba. Onowa is a Professor in the Department of Indigenous Education at the University of Victoria. She contributes to research areas such as Indigenous language revitalization, Indigenous education, early childhood bilingualism, cultural identity development, and early childhood care and education. She has also completed various research projects supporting the correlation between language revitalization and well-being in Indigenous communities. Her passion for Indigenous language revitalisation is evidenced by numerous community memberships, publications and research projects. Professor McIvor has been co-Chair of the WINHEC World Indigenous Research Alliance and contributed to the ongoing work related to the World Indigenous Research Journal. She has done exceptional work in advancing the outcomes of WINHEC through WIRA and the journal and her leadership has been extremely valued. |

| Professor Paul WhitinuiProfessor Paul Whitinui has worked tirelessly to advance First People’s engagement in education, research and authoring publications to raise awareness of issues within the wider community and in areas pertinent to human rights, wellbeing and social justice as it pertains to Indigenous Nations. In this regard, Dr Whitinui has done much to advance the development of a more culturally inclusive and respectful societal and education environment and in so doing, he has contributed to not only advancing the goals of the University of Victoria in terms of its engagement with First Nations People, but also that of the World Indigenous Nations Higher Education Consortium [WINHEC], the World Indigenous Nations University, the International Board of Accreditation, UNESCO and that of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Paul has been co-Chair of the World Indigenous Research Alliance and Chief Editor of the associated Journal. In his position as Chief Editor of the WIRJ, Professor Whitinui has provided exemplary leadership and dedication to the peer-review process, editing and formatting of the journal editions over the past six years and in so doing he has helped to address the perceived level of social and cultural disconnect that exists between what counts as peer-reviewed and what counts as knowledge in western and culturally aligned institutions and initiatives. The accomplishments of Professor Whitinui have been exceptional as they align to the goals of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in terms of mutual, appropriate and meritorious recognition being afforded to Indigenous and non-Indigenous policies and practices in education. |